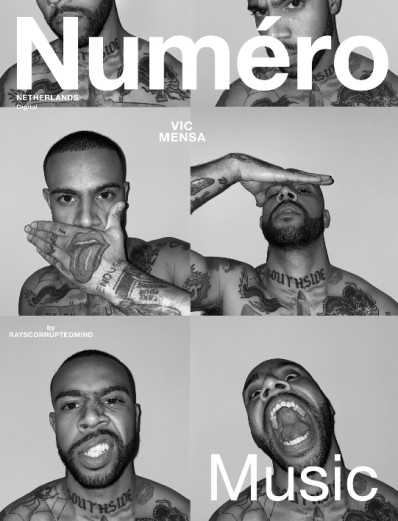

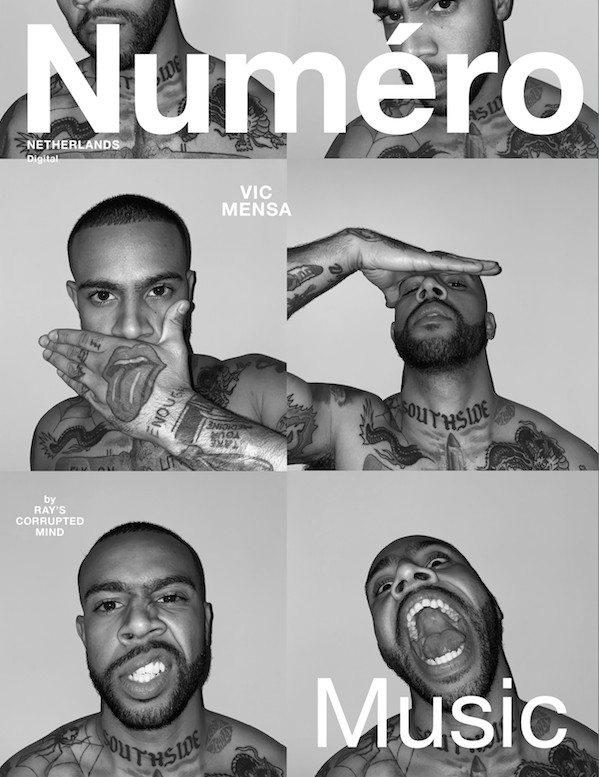

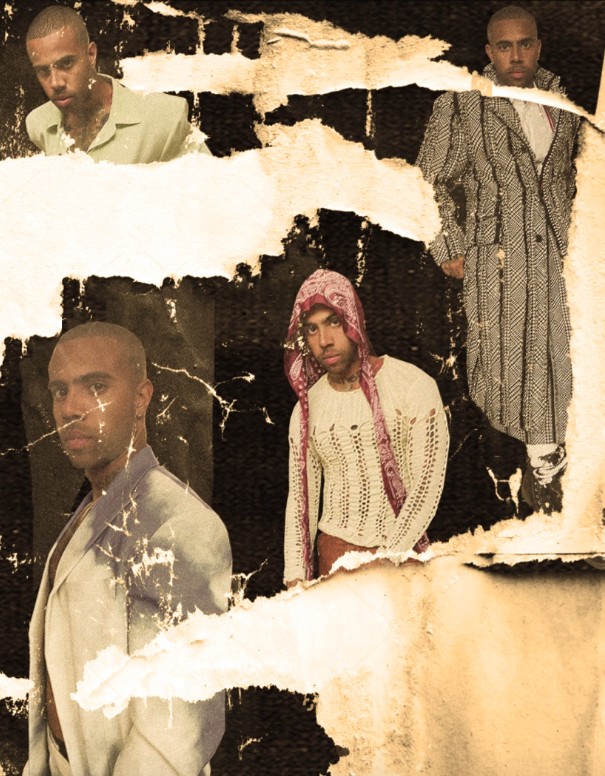

VIC MENSA IS OUR NEXT DIGITAL COVER STAR

The African in America

is an over the shoulder watcher

a look 4-ways before he cross the street-er

She is a barked command curver

curvy unapologetic hip switcher

He is a long-lost homeland forgetter

amnesiac pain burying law breaker

She is a louisiana gumbo cooker

houseless street walking home maker

The African in America is a stolen jewel, a grave robbed masterwork

beckoning to a past unknown

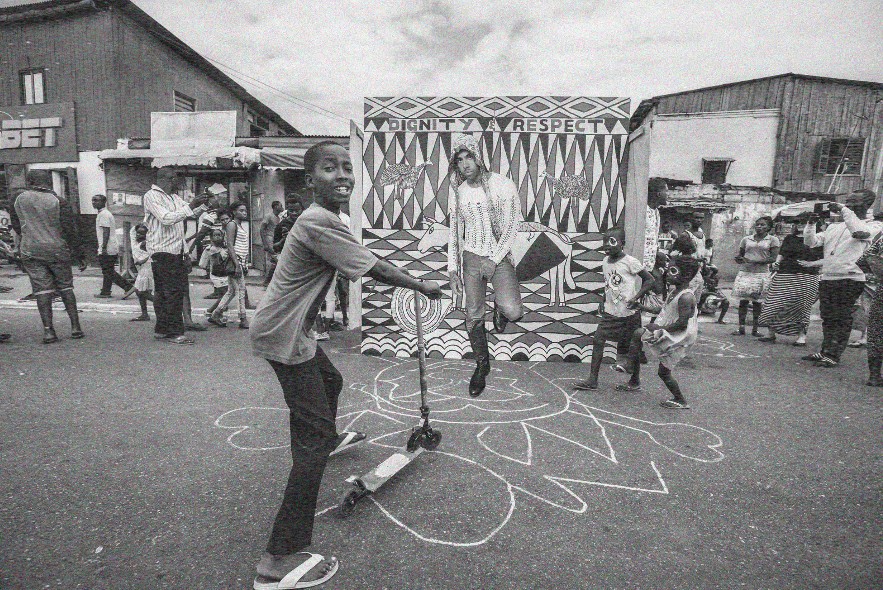

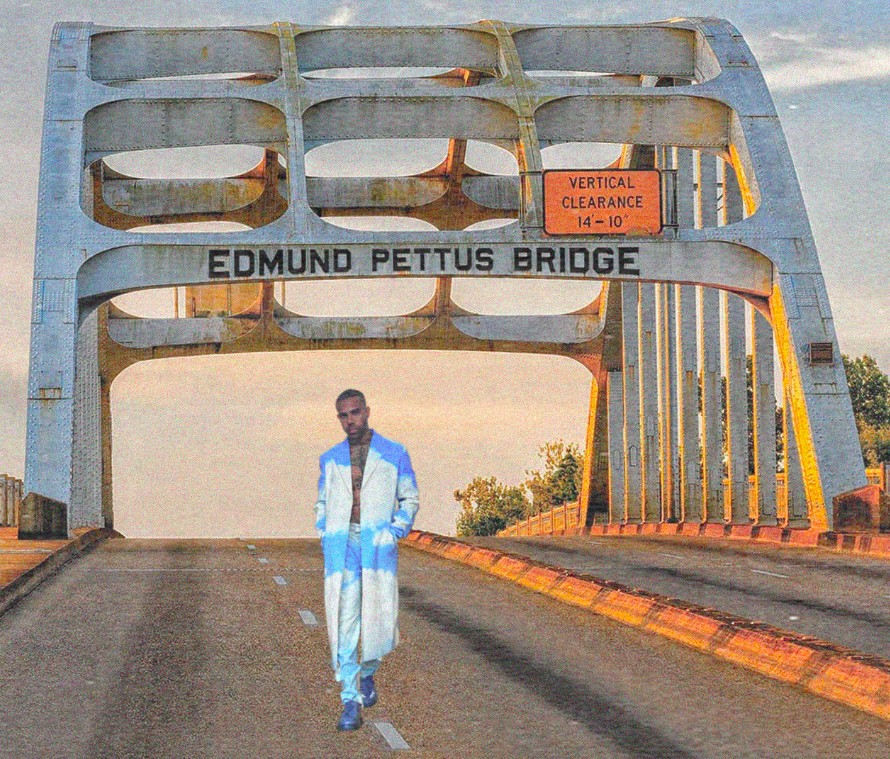

As we spill our blood in attempts to wash our hands clean of the scars and calluses accumulated from carrying America’s secrets, generation after generation of displaced Africans have radically envisioned Exodus. From Marcus Garvey to Sun Ra to Bob Marley, the innate longing to return has magnetically pulled Black people away from the tainted soil of our Lands of the free, often through the medium of artistic imagination. In our brush strokes, our rhythms and our silhouettes we have retained a cultural identity so intrinsically unbreakable that even we, at times, have been ignorant to its origins. I placed myself in a street scene in Ghana wearing Telfar beneath a sign reading Dignity & Respect as cultural acknowledgement of the synergy between the brand, my identity and the birthplace of my father. Telfar’s impact on the zeitgeist is undeniably African (unsurprising given his Liberian heritage), as well as unapologetically Black, Queer and non-conformist. It is worth noting that a utopian view of Africa eschews reality, and many of the oppressive constructs of American society are also deeply entrenched in the continent; homophobia, misogyny & neocolonialism to name a few. Yet, I believe, visualizing ourselves and our art within the context of our native heritage enables us to inject our ideals and our dreams of freedom into the imperfect present day iteration of the closest thing we know to liberation.

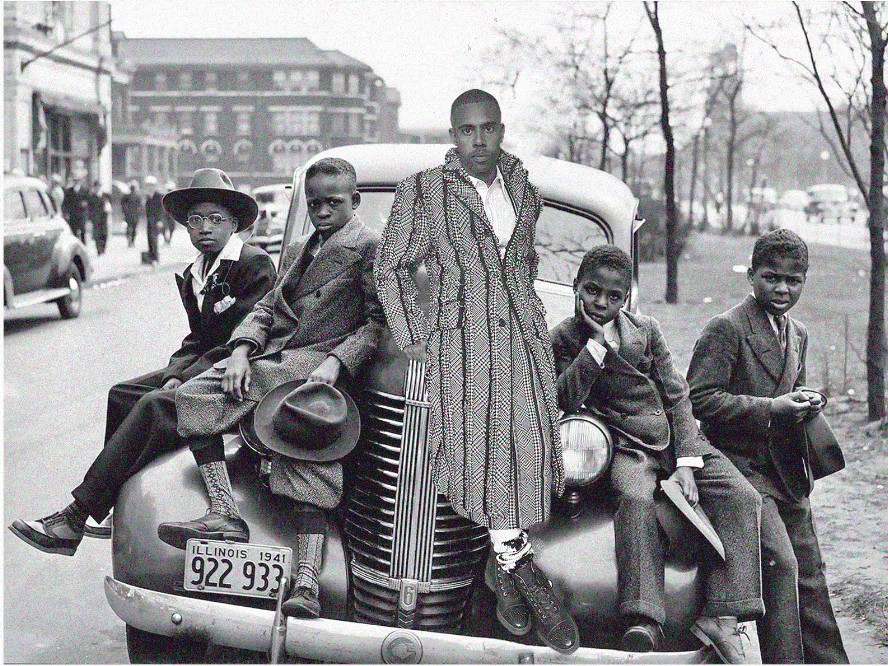

This summer as 47th Street bellowed in flames and Chicago’s Black Belt was once again engulfed in the rage of a caged people, images of Bronzeville’s historic past flashed through my mind like fuzzy white lightning, a beautiful illustration across a tormented sky. Desperation from a world-stopping pandemic, multiplied by traumatizing images of white supremacist terrorism created the conditions of a perfect storm, and widespread looting and rioting ravaged the South Side, where 95% of the population is Black but less than 10% of the business are Black owned. The historical precedent is there, and many of the remnants of the 1968 riots in the wake of Dr. King’s assassination still litter the streets; boarded up, decrepit buildings that look more like a war-torn third world country than America’s third largest city. And yet, things were not always this way. I’ve always marveled over the images of the bustling corners of 47th street, once the epicenter of a community known as the Black Metropolis. One of the most famous images is a black and white photograph of a group of young boys perched on the hood of a 1940’s automobile, dressed impeccably in their Easter best and poised with a regal confidence, if not a haunting dissociation in their eyes, as if they could foresee the troubled times to come. I placed myself at their helm, imagining myself leading a reversed funeral procession to a future where the streets of the Low End clamored not with gunshots and homelessness, but with enterprise and ownership.

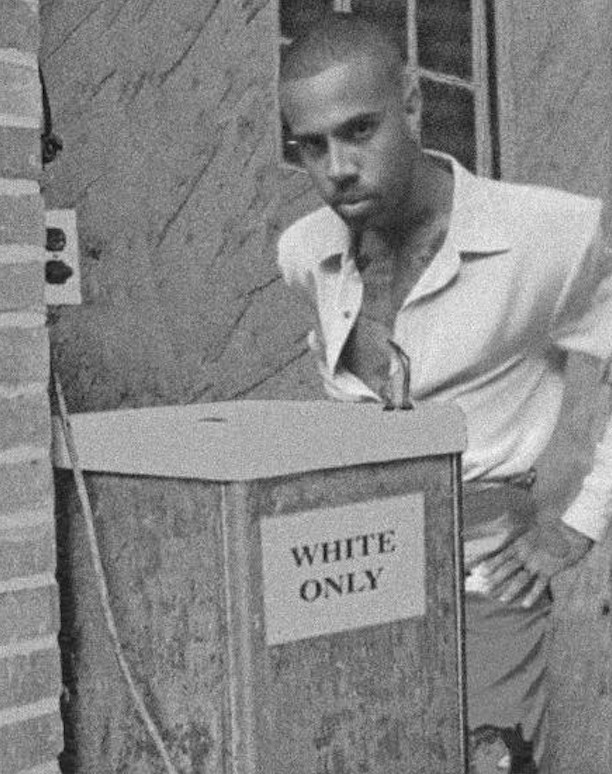

Separate but equal; one of America’s many last ditch attempts to maintain her legal stranglehold on the so-called sons of Job in the aftermath of her bitter loss of traditional chattel slavery. Of course we are aware that slavery was never truly abolished, but rather redirected into mass incarceration through the final sentence of the 13th Amendment, however, in the first half of the 20th century the societal chains were far more blatantly visible than they may be now, at least to the naked eye. It is within the very shackles of this social bondage that the predecessors of our current movements learned to thrive, to innovate and to resist. One such figure is Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the lesser known Black musician often credited as the “Godmother of Rock & Roll”, and one of the primary inspirations for my friend Kerby Jean Raymond’s Pyer Moss Collection 3. We imposed an image of me wearing Pyer Moss while drinking from a White Only water fountain to represent both the adversities our forebears overcame to shape the world as we know it, as well as the radical significance of our existence as artists on the highest levels of hierarchies not intended for us. – VIC MENSA

Team credits:

talent: Vic Mensa

photography: Ray's Corrupted Mind

stylist: Donte Mcguine

editor: Timotej Letonja